Advice for creating a portfolio of images that tells the stories of your travels abroad.

The post Focus On Culture appeared first on Outdoor Photographer.

]]>Better Travel Photos: Demonstrate Respect

Do your homework. Read up in advance on the places and people you’ll be visiting, including guidance on gestures or actions that are especially welcome or unwelcome in the local culture.

The Ganges River is sacred for Hindus, especially where it passes through holy cities like Varanasi. The reverence with which Hindus approach their “Mother Ganga” can yield beautiful images; be careful to respect that reverence. My image of a sadhu (holy man) was captured along the ghats (flights of stairs) that line the river. Other parts of these ghats are used for cremations, and photography is forbidden there.

Photographing from a boat toward the ghats in the early-morning light, you can capture reverent bathers reveling in the sacred waters. At the same time—even in the same frame—you can see people who are simply washing their clothes, bodies or hair as part of a normal daily routine.

When you’re capturing scenes of another culture, showing your respect for and commitment to understanding that culture will help you be accepted. This is especially important when your subjects use a language you don’t speak or understand. One of the simplest ways to demonstrate respect is to place yourself and the camera at the same level as a portrait subject, versus looking down (in the case of a seated subject or child, for instance).

Learning some key phrases in the local language is ideal, but pointing to your camera in a gestured request for permission to take a photo isn’t complicated and usually works. Sharing example images on your camera with your subjects will usually help build rapport.

Sometimes, a reluctant subject is just shy and can be gently and respectfully cajoled. For instance, you can take a photo of a nearby pet or object and share it, and often that will break the ice. Parents and grandparents are usually eager to offer their children for photos. Sometimes the children are the most interesting photographically; at other times, the adults.

Seek Out Festivals And Celebrations

Consider scheduling your visits to overlap with potentially photogenic local festivals. Festivals often have many key ingredients for engaging imagery, including happy people who are pleased to share their joy with you, colorful and unique clothing or festival settings, and a celebratory mood overall, which can translate to lively images. Also be on the lookout for celebrations that you weren’t aware of in advance.

In some rural areas, such as the tribal areas of the state of Chhattisgarh in India, villagers (perhaps encouraged by a donation to the village from your local guide) may be willing to perform traditional rituals and dances specifically for your group. During a visit to one of these villages, we had several hours with multiple groups of dancers. Such arrangements can present rich possibilities for action and portrait photographs.

Some festivals get so popular that they are almost overwhelmed with other tourists, who can mar the authenticity of a scene. Consider the Paro Tsechu festival in Bhutan, typically held in March. While all the ingredients mentioned at the beginning of this section are present, there are also hundreds or thousands of tourists, and it can be difficult to capture a festival image without them. Meanwhile, similar tsechus and other festivals are held across Bhutan at other times of the year. During our two June weeks in Bhutan, we photographed three beautiful tsechu festivals in out-of-the-way towns and saw very few tourists. But we needed to invest in day-long drives on precarious mountain roads instead of driving an hour from the Paro airport to the tsechu festival there.

During a visit to Jaipur, India, we headed out for what we expected to be a routine late afternoon of street photography. We started following what seemed to be a wedding procession—always an exciting proposition in India—along the streets. We learned that this Ganguar festival included an event that casts girls and boys as brides and grooms and celebrates simulated weddings for them, complete with elaborate clothes and makeup. That “wedding procession” led us to a park area with dozens of “wedding parties” all begging to have their pictures taken!

One challenge with photographing such dynamic events is that you may need to shift on short notice between wide-angle and telephoto lenses. To maximize your flexibility, you can carry two bodies, each mounted with one of the two lens types, say a Canon EF 24-105mm F/4L IS USM lens on one body and a Canon EF 70-200mm F/4L IS USM on the other. I carry the two bodies on a harness so that I have instant access to either focal length range as necessary for the image opportunities I spot.

Zoom lenses give you critical framing and subject isolation flexibility. In the particular pair of lenses above, the longer reach of the 24-105mm lens, compared to a common 24-70mm alternative, gives you more telephoto range on your wide-angle camera, potentially saving you some camera/lens swaps.

Image stabilization can help you preserve the convenience of handheld shooting, even in low light and even for lighter and smaller lenses with relatively slower apertures like ƒ/4. With a slower lens, you may need to use higher ISO settings, but with modern cameras like the Canon EOS 5D Mark IV, such settings work well. While shooting in aperture priority to control your depth of field, you can set a minimum shutter speed for the expected subject activity level and have the camera automatically boost the ISO level to achieve that speed.

Look For Unusual Perspectives

The annual Holi festival in India is a riot of colored powder and paint that is brimming with photographic possibilities. Even in this subject-rich environment, you can up your game by finding an unusual perspective to capture the action.

To gain the perspective of my image taken in the Vrindavan temple (above), we climbed to a balcony and shot down toward the temple floor. Tripods are out of the question in the hubbub of Holi, so we steadied our cameras against a balcony railing to keep the pedestal sharp, despite the one-second exposure. I sought to capture the worshipful (but frenetic) motion I saw below me.

Holi presents special challenges in protecting your camera equipment—and you. We enclosed our cameras entirely in low-cost clear plastic OP/TECH Rainsleeves. The sleeves were taped to the lens at the filter ring, where the front element was protected by an inexpensive UV filter. We operated the cameras entirely through the rain sleeves and discarded them at the end of each day.

If you plan to shoot Holi, take care of your body as well. I wore contractor safety glasses to protect my eyes from flying liquids and powders. I saw western visitors wearing snorkeling goggles. You may find such protections unnecessary. With the help of our local guide, I acquired a local Indian white outfit, wore it every day during the festival and left it behind, no longer white. Beware the risks of jostling crowds; consider leaving your cell phone and valuables in the hotel safe.

Plan Productive Wandering For Better Travel Photos

One way to take the pulse of a place and its people is to wander around. Look for places and times for your wandering that can maximize your photographic yield.

In a booming Chinese city, tall modern buildings and conventional urban street looks can dominate many scenes. Is there an “old town” section that may be more representative of traditional life in the area? Maybe there’ll be an opportunity to juxtapose old homes with new skyscrapers or busy construction sites? We found exactly those possibilities in Kashgar, China (population 4+ million).

If you stop at one of those touristy handicraft stores, is there an area out back where the handicrafts are produced? In northern Vietnam, we found such an area behind a massive pottery shop, with dusty workers and dozens of symmetric rows of shapely pots.

Rural villages are often most active in the morning and late in the day. Happily, that’s when the quality of light is typically best as well. As you wander, keep an eye out for inner courtyards with interesting activity; often, locals will graciously welcome you into them.

In Foreign Territory, Arrange A Local Guide

An English-speaking local guide can help you communicate with other locals much more effectively than you can on your own. That’s true even if you’ve mastered a limited set of guidebook phrases or have a smartphone translation app (though such phrases and apps can definitely be helpful). If you aim to understand the culture you’re visiting or the ceremony or festival dance that you’re photographing, a local guide can be invaluable. The quality and depth of the verbal and image stories that you tell will definitely benefit.

Remember the extended exposure scene from a Vrindavan temple during the Holi festival? We would likely have been hard-pressed to gain access to that balcony at all, at least on reasonable terms, without a local guide to negotiate on our behalf.

As we practiced productive wandering in Chhattisgarh, an India village, our local guide helped us to communicate with villagers. They welcomed us into a courtyard where one was cranking a fan to separate the desired crop from the undesired chaff.

If you find an especially photogenic setting, either by yourself or with the help of a local guide, another option is to wait for interesting characters to come into your scene on their own. On a trip to Yunnan province in China, we were based for several days in a small village. Most mornings, we did pre-breakfast walks, looking for ways to take advantage of the terrific early-morning light. One effective strategy was to find an attractive background scene with good lighting on a fairly active village street and wait for interesting villagers to come into the scene. Some declined my gestured requests for permission, but most accepted.

Managing Logistics: On Your Own Or With Help?

Some photographers choose to organize their own trips, presumably with the help of a local agency for international travel. Though most of my international photography has been done as a member of a photo-focused tour group, some has been done with other approaches. One trip to Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos and Thailand was organized around a scheduled group cruise on the Mekong River from Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam (formerly Saigon), to Siem Reap, Cambodia (site of Angkor Wat). We added time with a local guide in northern Vietnam before the cruise and time on our own in Laos and Thailand after the cruise.

Joining a photo-focused tour group can yield real benefits. You can gain from the tour leader’s experience with high-yield photography sites at each locale, including how to take advantage of the best early and late-day light, as well as when and where to find the most photogenic activities. Many photo tour leaders will provide valuable critiques that can help you grow photographically. These critiques may be impromptu discussions at the back of your camera during a shooting session or organized group sessions at your hotel. These and other benefits typically more than offset the portion of the tour cost that helps the leader earn his or her living. Look for tours with a low ratio of clients to leaders.

Share Your Most Compelling Stories

Social media posts are one way to share, of course, but I’ll focus here on approaches to sharing that are less ephemeral.

Consider creating a photography website that hosts your travel stories, perhaps with some words to augment your images. Various companies like SmugMug provide photo website creation and hosting services for a modest annual cost. You can choose among a wide range of themes that control how your site looks and how your images are organized and accessed. You will likely have the option of offering your images for sale on the site as well.

Many photography portfolio websites have little or no verbal commentary. I recommend that you consider complementing (and, I would argue, likely deepening and enriching) your image stories with verbal stories by also offering a supplementary blog, brief captions on your images or both.

Also, consider getting serious about creating well-crafted prints of your most compelling images and even mounting coherent public exhibits of well-curated groups of images. For some photographers, a photograph is not real or complete until it’s printed. Ansel Adams considered a photographic negative to be the score and the print to be the performance of an image. Don’t you want your images to be performed for an appreciative audience versus sitting silently on your hard drive or website?

If you’re not yet ready to do a solo exhibit in a gallery setting, there are many more accessible ways to arrange an exhibit of your travel story, including at local restaurants, other businesses or government buildings. The hard work of capturing, post-processing, curating, printing, framing and hanging an exhibit of your images can certainly be challenging. But the process and the results can also be hugely rewarding to you and a pleasure to share with your family and friends as well.

One exhibit I did recently was called “Connecting with Reverence.” All the images were from India, including several that are also used in this article. I sought to show some of the ways in which the residents of this vast land demonstrate reverence. I can’t share the physical exhibit with you, but here’s a link to the online gallery with the images and complementary stories: www.remarkableimagery.net/Exhibit-Connecting-w-Reverence/i-JZjbM3k.

Connecting with the world can be immensely rewarding, both personally and photographically. I hope that these recommendations help you broaden and deepen those rewards—during your travels and after your return home.

See more of Mark Overgaard’s work at remarkableimagery.net.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

Eyes On The World

Travel photography tips for documenting places and cultures. Read now.

The post Focus On Culture appeared first on Outdoor Photographer.

]]>Five inspiring subjects to add something new to your portfolio.

The post Jump Start Your Photo Bucket List appeared first on Outdoor Photographer.

]]>Hiking A Volcano

One of my first and longest-held photo bucket list items is hiking a volcano. It is so amazing to look into the Earth’s core and see molten rock bubbling, exploding and running into the ocean, creating brand new land. I will try to explain the glow, the sounds of the explosions and crackling of the 2,000-degree Fahrenheit lava as it flows down the path of least resistance. The image here is from a trip I took to the Big Island of Hawaii.

Hiking out to reach the ocean entry or flying in a helicopter over the Pali (hillside) will have you rising in the middle of the night to be out and in place during the best viewing time, the transition from night to day. If conditions allow hiking, I generally begin my hike around 3 a.m. since it may take nearly three hours to reach the coast. It is not always accessible or safe by hiking—the only way to determine this is to hire a guide to safely take you out and back. This is not something that you should try on your own.

My absolute favorite way to reach the ever-changing lava is by helicopter. I fly with a very knowledgeable team of pilots who know the lay of the land. They can put me directly over the lava flow, and, if it is safe, provide me a perfect view of what breakout is happening. Going by helicopter means being at the airport about 90 minutes before sunrise in order to begin capturing imagery as soon as the light is right.

When flying in a helicopter or small plane, you will want to minimize what you take with you. There probably won’t be room for a camera bag nor a good opportunity to change lenses inside the helicopter, so do a little bit of pre-visualizing to determine what lens you might need. I fly with a UV filter on my lens, and I start the flight with freshly charged batteries, ample digital media and no lens hood or anything that could come off of the camera due to the wind created with the doors off of the aircraft. We don’t want anything falling out of the copter as we move along.

Within a moving or hovering aircraft, you will need to be ready at all times to capture images. The amount of time that you are in the air will depend upon your budget, so be ready to snap images quickly.

ALSO SEE

Boom, Baby!

Exploring the explosive beauty of Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park. Read now.

There is one more option to see the lava enter the ocean, and that is from a boat that will bring you within 30 to 50 feet of the flow, depending upon the steam that is directed by the wind. This steam is sulfuric, and the boat captains did a great job of steering us all away.

In a moving vehicle of any kind, I use mostly aperture- or shutter speed-priority modes in conjunction with Auto ISO. This allows me to maintain my shutter speed, regardless of the light level. Setting my shutter speed to 1/2000 sec. will guarantee solid, sharp imagery. I do not need much depth of field, so I will select an aperture in the “sweet spot” for my lens—typically about two stops down from wide open. I also enable the image stabilization to help eliminate vibration and any movement from the vehicle.

Whichever method that you choose, you will be ecstatic seeing this fantastic example of Mother Nature.

Chasing A Monsoon Storm

Living in the southwest desert offers certain benefits photographically. Here in Phoenix, Arizona, we have a bucket-list season every summer called monsoon. Each day, we have isolated, photogenic “cells” build during the heat of the day, culminating in a daily thunderstorm.

These monsoon thunderstorms are lightning-generating and often kick up dust storms called haboobs. This is the time of year where morning, noon and night provide excellent weather-related opportunities for amazing sunsets, thunderstorms, dust storms and dust devils that make for incredible landscape photographs. Dimensional cumulus clouds will be your subjects from sunrise throughout most of the day. Once those cumulus clouds start to tower, you will see lightning develop and transform the puffy, pretty clouds into dramatic storms that are fun and easy to chase, providing colorful sunsets that transfer into the evening storms. You will have long, productive fun days with many photo opportunities.

I most often capture my landscape photographs on a tripod and in aperture priority-mode to control the depth of field. I use a cable release to fire the camera so I don’t move it, especially important if the exposures start to get long later in the day or at night.

Flying In A Hot-Air Balloon

Who hasn’t dreamt of the romance and beauty of flying in a hot air balloon? I was mesmerized from the first hot-air balloon event that I attended in Norwalk, Connecticut, many years ago. I was so taken with the concept of flying in a hot-air balloon that a few weeks after I captured my first images, I drove to another balloon event in upstate New York and ended up flying. It wasn’t long afterward that I would buy a balloon and found a pilot to teach me how to fly.

Earlier this year, I had the opportunity to photograph the balloon capital of the world, Albuquerque, New Mexico, at the largest gathering of hot air balloons in the world, the Albuquerque International Balloon Fiesta. More than 600 balloons flying every day, weather permitting. They fly in the morning when winds are gentle and temperatures are cool.

There are so many activities for you to capture there. There is Dawn Patrol, where balloons lift off in the dark, a laser light show and finally the stars of the show, the hundreds of hot-air balloons filling the skies. Since we are photographing in low-light conditions, I bring fast lenses (ƒ/2.8 or faster) so I can use as low of an ISO as possible to make images in the dark as the Dawn Patrol inflates and then flies into the pre-dawn sky.

Once the balloons begin to inflate, you will find a huge smile on your face as you have the chance to create backlit images of the inflating waves of balloons. You will find colorful fabric being inflated by gasoline-powered fans beckoning you to come and make images. Before long, the skies will fill with those gorgeous balloons, providing you unending possibilities of spectacular compositions.

If you are able to spend a few days at Fiesta, you should consider making arrangements to fly in a hot air balloon and shoot from the air, passing over other balloons as they inflate. The experience will amaze you.

Witnessing Aurora Borealis

Another of my absolute favorite dreams, looking up to the heavens and watching the sky dance! Witnessing the northern lights has been at the top of my bucket list since I was a teenager. To view and photograph the Aurora requires some planning.

First, you will find yourself packing lots of warm clothes since you will most likely be traveling to a city near the Arctic Circle. The warm clothing comes into play because you will be traveling between mid-September and mid-April, when the winter nights are long and cold near those latitudes. Places to see the Aurora Borealis include Alaska, the Northwest Territories of Canada, Iceland and Nordic countries like Finland and Norway.

One unusual thing is having to sleep during the daylight hours, since you will be awake searching for the "lights" through the night. Meals will be adjusted a little bit differently because of the long nights—be sure to bring snacks to hold you over. What makes these efforts worth it will be the spectacular, omnidirectional show of color across the sky.

Since all images of the Aurora will be taken in the dark of night, sometimes with the moon above the horizon and other times with no moon, you should always use a sturdy tripod to support your camera. I recommend choosing a fast wide-angle lens and using a cable release.

You will want to consider working with high ISOs like 3200, 6400 or even higher, in order to keep your exposure times as short as possible. The Aurora is always moving and changing. I would suggest keeping your shutter speeds relatively fast for night exposures (that could be one second long or up to 30 seconds) so that you can freeze the dancing of the Aurora.

As you are scouting the shooting location, look for some beautiful elements to act as a foreground for the moving colors across the sky. Providing multiple layers in your composition will help hold your viewers’ attention.

Capturing The Milky Way

Here is another opportunity to head out in the dark of night to capture the vibrancy and colors of the nighttime sky. The Milky Way and its spectacular galactic core visit the northern hemisphere from mid-April through mid-September.

There are not too many nights that are Milky Way-friendly, so you’ll want to plan ahead. What is necessary is a clear, dark sky. Many of us have to drive a fair distance away from our light-polluted neighborhoods. The best time to make images of the Milky Way is during the new moon, when there is no moon and the sky is the darkest. Early in the season, the Milky Way rises in the eastern sky and slowly anchors itself in the southern sky.

Learn how to successfully photograph the Milky Way.

I recommend using a wide-angle lens, again on a tripod and with a cable release. Basic exposure settings would be around 30 seconds. Pack a cooler and a chair to be comfortable outside in the dark, enjoying the beauty of the galaxies in front of you.

To me, the best part about a bucket list is that it’s never too soon to get started, nor is it ever too late to begin. Once you accomplish one of your bucket list items, you can simply add a new one to the list. It’s a list with no end, so start yours today.

See more of Ken Sklute’s work at serendipityvisuals.com.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

Misadventures In Landscape Photography

How a shared passion for photography can create lifelong friendships. Read now.

The post Jump Start Your Photo Bucket List appeared first on Outdoor Photographer.

]]>Travel photography tips for documenting places and cultures.

The post Eyes On The World appeared first on Outdoor Photographer.

]]>

Focus

While real estate might be all about “location, location, location,” strong travel photography should go deeper. For instance, instead of a general story on Japan, I focused on its people’s fascination with onsen (hot springs) in my book The Way of the Japanese Bath. For a magazine feature, I retraced the steps of the haiku poet Basho on the Nakasendo, one of the two ancient routes connecting Kyoto with Edo — modern day Tokyo.

For France, an obvious hook is its incredible wine regions, including Burgundy, Bordeaux, Côtes du Rhone and so on. Angles within those range from a focus on the winemakers themselves to the traditions and craftsmanship of French oak barrel coopers.

Wherever the destination, seek out stories that give both you and the viewer an inside look into a culture by focusing on a person, a ritual or a unique aspect of history. Anniversaries of historic events in particular are fertile soil for fascinating photo opportunities.

Location & Timing

Whether it’s the Eiffel Tower or a yurt in Mongolia, photographing architecture is all about the position of the sun, requiring us to be at the location at the right time of day. Typically this means when the sun or its afterglow is illuminating the front of the subject.

Using the sun as a backlight and silhouetting the structure or a unique landscape can work when they have extreme geometric shapes and your main focus is to capture its form. To create a silhouette of people crossing the world’s longest teak bridge in Mandalay, Myanmar, I hired a rowboat to get into a position where I could have the people stand out against the sky.

My assignment in the Black Hills of South Dakota was greatly assisted by knowing the best times to photograph Mt. Rushmore (in the morning with direct sunlight) and the Crazy Horse Memorial (in the afternoon and evening). A spectacular light show at the memorial capped off a great day of shooting. I also spent two days in Deadwood to photograph the local culture and folklore. I timed the visit to coincide with the historic town’s annual Wild Bill Days festivities.

Landscape photographers are constantly checking the latest weather reports and carefully timing their outings for optimal conditions. But optimal doesn’t necessarily mean blue skies. A sky full of clouds or an approaching storm can be full of drama. Look at the magnificent black and white imagery of Mitch Dobrowner to see how powerful the latter can be. I’ve found that a graduated neutral density filter is an important tool in these situations or for taming a bright sky.

I also carry polarizers and a 9-stop ND filter. While light loss is a necessary evil with polarizers, neutral density filters are used precisely for that purpose. They are vital when a long exposure in a daylight scenario is required. The beautiful painterly results created with a slow exposure of a waterfall is a classic example.

Broad landscapes and cityscapes are often used as establishing shots for a photo essay. For my Venice Grand Canal establishing shot, I waited for a gondola to pass into the frame. The phrase “good things come to those who wait” has definite photographic applications. Waiting for the right combination of elements to come together rather than running from one location to another definitely has its virtues, and it can be useful in both urban and natural environments.

Photographic history is full of examples of timeless images taken where a photographer put themselves in a position and then waited for what Henri Cartier-Bresson termed the “decisive moment,” the instant when all the elements of a potentially great image come together. If we heed this, we can avoid uttering, “This photograph would have been great if…” Wait for the “if.” French photographer Willy Ronis once told me that shooting like a mitrailleur — a machine gunner — was the best way to miss a picture.

For the Venice shot, I also envisioned how the scene would look from a higher vantage point so I could avoid having the gondolier’s head merge with the background buildings. What are the odds of achieving the perfect angle where you happen to be standing and at your exact height? It’s important to be flexible both physically and mentally to get to the right position.

While my NIKKOR 14-24mm f/2.8 and 24-70mm f/2.8 are my usual lenses for architecture and landscape/cityscape establishing shots, telephotos can be used to compress elements such as those in my image of a street scene on a rainy day in Havana.

People & Cultures

When it comes to intimate photographs of people in a travel photography context, the “trying to sneak a picture with a long lens” approach actually creates more of a distance between the photographer and the subject, no matter how much one zooms in. Getting through the fear factor of approaching a stranger, especially one who doesn’t share a common language, can be daunting yet can yield not only stronger photos but also a deeper personal exchange and understanding between cultures. Dramatic environmental portraits (documenting a person in surroundings that relate to who they are or what they do) and the “eyes are the window to the soul” portraits are almost always the result of human interaction.

A few words in a local language can act as one of the keys to unlocking a potential photo op. I’ve found that listening to a Pimsleur foreign language CD to pick up some words before a trip to a non-English speaking country is well worth the investment of time and brainpower.

Back to photography techniques, shooting portraits in open shade can be utilized any time of day. My “eyes are the window to the soul” example of a young girl in Sapa, Vietnam, was shot at the entrance to her family’s store, just out of reach of the glaring noonday sun. The background was thrown out of focus with my 85mm lens set at f/2.8. Dramatic portraits are often achieved with very shallow depth of field and focus on the eyes.

My image of a traffic officer at work in Pyongyang, North Korea is an example of an environmental portrait. Whether it is of a sheepherder with his flock, a sommelier in a wine cellar or an artist in her atelier, these types of photographs add an important, and in many cases, a vital human element to a travel story. In terms of how much of the person to include in the frame, a three-quarters, or “cowboy” as it’s known in the movie industry (cropping below the guns), is often a good percentage of the person to include in the frame. Typically a little more depth of field and a wider lens is needed to convey the feeling of the background, but not so much that it pulls the attention away from the subject.

In most situations, I shoot in aperture priority mode because I want to constantly be aware of, and in control of, my depth of field. All the while I am keeping an eye on my shutter speed to not let it fall below the minimum that’s required for a given situation. To work expeditiously, if the exposure is either too bright or too dark, I’ll normally use exposure compensation rather than switching over to the manual exposure mode.

Detail Shots

The “devil is in the details,” but often so is the beauty. Intimate shots are a nice change of pace from the wider establishing and environmental portrait images. Close-ups of subjects such as food, flowers, butterflies, coins and jewelry often necessitate the use of a macro lens such as my NIKKOR 105mm f/2.8. Diopters, also known as close-up filters, are a cheaper alternative.

Food in particular is an important part of any travel experience, but capturing successful images of food is not as easy as it may seem. Food photography is a specialty in the professional photography world for good reason. For food magazines and food advertising photography assignments, stylists are often brought in to help prepare the presentation for a photographer to capture. When it comes to travel photography, it’s not practical to be traveling with a food stylist, so chefs and their assistants can act in a similar capacity. I solicit their advice on the best angles to highlight their creations. I often set up the photo shoot at a restaurant in advance, usually in the later afternoon so I can take advantage of diffused angular window light. A macro lens, tripod, cable release and silver/white reflector opposite the window, with my camera in Mirror Lockup mode, work as a team to capture the shot. I never use a reflector with a warm, gold or orange side because it will create an imbalance in the color temperature of the overall scene.

Lighting On Location

My goal when using flash is to make the image still feel within the realm of a naturally lit photograph — “natural” meaning that even if it’s indoors, it will feel like it could have been taken using existing light sources. I never want my images to scream “flash!”

I try to match my lighting to the mood to get the most out of the subject, whether it is by softening shadows or creating harder ones in a realistic way. One of the reasons for fill flash is that it’s not always possible to be at the right place at the right time in terms of ideal ambient light conditions. Since “raccoon” eyes are unflattering except on those furry procyonids, flash fill is an extremely useful tool for environmental portraits when open shade or backlighting is not possible.

Since most flashes fire at a cooler (more bluish) daylight color temperature than the prevailing ambient light in many travel photography scenarios, I often have a slight warming gel — a 1/4 or a 1/2 CTO (Color Temperature Orange) — over my flash, especially in the early morning or later afternoon to create a correct color balance.

In addition, I usually hold my flash at arm’s length at a 45-degree or higher angle off the camera and trigger it wirelessly. This further helps to create a more natural and realistic scene by making the shadows drop down behind the subject. I also often put a Gary Fong Lightsphere Diffusion Dome or other light-modifying accessory over the flash head to soften the light.

Keep in mind when using color gels or setting a white balance that the goal is not always to capture what would be a “proper” color balance — a white piece of paper reproducing as white, for example — but rather the appropriate color balance for the given situation. For instance, a candlelit dinner should have a lot of warmth, while a mid-winter high arctic scene would work well with an ice cold bluish tint.

The Presentation

A travel photo essay is basically a story of a journey told through photographs. Like any story, there needs to be a structure. It should have a strong beginning, middle and end. Like chapters in a book, the images should relate to each other as you move through the story and come to a conclusion. If you’re documenting a journey for yourself rather than a publication, I highly recommend producing a book of the experience through companies such as Blurb.

A Final Thought

I’m sound asleep at the Hard Rock Hotel Tenerife in the Canary Islands when the alarm goes off at 5:30 a.m. The last thing I want to do is get up after three flights in the last 24 hours. Maybe it’s the second-to-last thing — I definitely don’t want to miss a great photo opportunity. The rising sun won’t wait for me. We as photographers have an obligation not to be lazy. We get award-winning shots by hitting the shutter button, not the snooze button.

The post Eyes On The World appeared first on Outdoor Photographer.

]]>Taking an investigative approach to a place will improve your travel photography.

The post An Archaeologist’s Perspective appeared first on Outdoor Photographer.

]]>

The zodiac boat hurtled over the waves, each crash showering us with the cold, salty waters of the Black Sea. I could no longer see the bobbing lights of the American research vessel we’d just left. We had launched an underwater robot whose duty it was to comb the ocean floor in search of ancient Greek and Roman shipwrecks. Ahead, two more miles through the stormy waters, was our home for the project, a Ukrainian ferry that was housing part of the research team.

Except for the stars and occasional flare of a cigarette, we were alone in the dark, all conversations muffled by the motor and the splashing waves. This moment, representing my first introduction to the life of archaeology, is burned into my mind as one of my more vivid memories. On that tiny boat bouncing through Ukrainian waters, I embraced my calling—a never-ending desire to wander the globe, to study its people, landscapes and animals. I had begun a fascinating journey to understand the world.

What does archaeology have to do with taking better travel photos? I am an environmental archaeologist, a subspecialty of a profession that studies past human life, in which I explore the interrelationship between man and environment. For the past 15 years, I have both participated in and directed archaeological research projects looking at the connection between people and nature.

Archaeology is a diverse field and includes ancient cultures, human evolution, technology and other obscurities such as human interaction with glaciers or the study of bugs from prehistoric graves. There is an ancient topic out there for anyone with an inquisitive mind. I specialize in mountain communities but am interested in the full spectrum of ecosystems—jungles, deserts and tundra have in their own ways impacted that mysterious component of human life that we label as culture.

When not researching ancient peoples, I work as a photographer. I collaborate closely with museums, laboratories and excavations to help tell stories of science and discovery. Scientists are not always the best at explaining their work, and photography offers a clear visual translation of highly technical topics. Archaeology is an interesting field in that it requires a complete context to fully understand an excavation. The landscape, climate, geology, food resources, animals and modern communities all must be considered.

It is this concept of all-inclusiveness that also makes travel photography a unique practice. To tell a complete story of a location, all of that place’s characteristics must be explored. Because of the close similarities between approaching archaeology and travel photography, I’ve found the two to be a natural and fascinating duo that, when combined, can create a powerful and detailed narrative.

Since that first project in the Black Sea, my job has led me to roughly 30 countries on four continents. I’ve lived on boats, in villages, with bears and amongst teargas. Describing my career tends to evoke the travel montage from “Indiana Jones,” but it’s never that romantic. Excavating in the snow or at 120 degrees hurts, there are endless pages of paperwork to be written, I collect tropical diseases like Boy Scout badges, and I frequently must do battle with that lethal war machine, bureaucracy. Nevertheless, the perks are spectacular. Traveling the world as an archaeologist has not only allowed me to visit locations that I would have never imagined, it has also taught me how to explore and perceive different places in a unique way.

Slow It Down For Better Travel Photos

I often feel that we move through the world too quickly. While traveling, we acquire superficial glimpses of life and of places, but we don’t truly get to know them. Great photography is all about patience, and I think that this mantra is especially important when traveling. If we can slow down, embrace details and really focus on one community or a particular theme, it becomes possible to work the scene, as you would with a landscape, and to explore it in greater depth.

Between 2011 and 2012, I spent several months living and working out of a Maya village in the remote Toledo district of southern Belize. Along with my wife and fellow archaeologist, Rebecca, we were working for Dr. Claire Novotny (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill), who was exploring a dense part of jungle for previously unknown Maya sites. We were stationed in an old British farmhouse, a crumbling skeleton of cement walls with no doors or windows but plenty of bugs and the occasional snake. Every morning we would rise before the sun, meet with local guides, assemble some excited students from the village school, and head into the rainforest seeking signs of something ancient.

Working in the rainforest with different villagers every day was like getting a series of behind-the-scenes tours. We got to know what made the village function and what didn’t. We learned about rivalries, friendships, traditions and taboos. We formed a bond with the community, something special and much deeper than could have been attained as tourists simply passing through. By combining our observations with the archaeological discoveries, it became possible to tie the modern community with those of the past and to see what events and situations shaped the culture and village we had come to love.

My time in Belize taught me the importance of speed and scale both when traveling and while photographing. Moving through a new place, especially somewhere exotic, can be overwhelming and difficult to digest. However, by slowing down, focusing on details and allowing a single location to reveal itself, it becomes possible to see it more completely. This is particularly helpful in chaotic locations like a market or train station, where over stimulation can make it difficult to focus. Slow down, take a seat, and let the scene unfold by itself.

Archaeology teaches us that every community is a complex system with multiple players. In order to understand a place, we must consider what goes into making it function, who the characters are and what events in the past transpired to create the scene that is visible today. Context is key in this matter, and without it we are left with a stack of pretty pictures or broken pots, void of a story.

Get Off The Beaten Path

Moving through the world as a field scientist provides opportunities that are not always available through regular tourism. There are excavations in every corner of the world, even Antarctica, and on most occasions, they are located far off the beaten path. There’s something special about being planted in a place you otherwise wouldn’t visit, some frontier town or village, and given the opportunity to truly discover it, to intimately know what makes it special and unique.

Every single place on the planet where people have settled, past or present, has a story to tell. Highlights on the tourist trail might possess the most famous stories, but if you are willing to ask the right questions, use a different perspective and take the time to listen, anywhere can produce a stunning narrative or image. The relatively unknown places also tend to be the most surprising. Somewhere popular or famous always has a reputation that precedes it and will let us know what to expect before we even arrive. A remote or unexpected location can be a blank slate that allows true exploration and discovery to transpire.

Sometimes it isn’t always possible to leave home, travel across the world and plant roots in a new place for months at a time. But traveling slowly does not always mean staying in one location; it’s not an itinerary recommendation, it’s a mindset. Visiting multiple locations can be just as revealing as remaining in a single place. It can allow the development of a narrative that extends beyond border and culture. While it is important to study a place in detail, it’s equally crucial to understand how that place compares to others and fits into a larger story.

One of my favorite aspects of archaeology is in noticing similar behaviors, adaptations, or rituals in societies that are on opposite ends of the world. When traveling, it is often easy to romanticize the foreign or exotic and to focus on the differences between cultures. To me, though, it’s the similarities, the little things that we all do, that I find most fascinating.

Rediscover The Familiar

While archaeology has provided many opportunities for me to see foreign places, I recently returned to my home town after almost a decade away. Having grown up in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, I began my career by, and have heavily focused on, researching prehistoric peoples of the nearby Teton and Wind River Mountains. These are all locations that I have known and explored since I was young but have now learned to see in an entirely new way.

Cees Nooteboom once wrote a beautiful passage about how after visiting Venice for the first time he was saddened, knowing that the moment of excitement and wonder was forever stolen. No matter how many times he returned, that instance of discovery and his feelings at first sight could never be recreated. I used to sympathize with Nooteboom, believing that revisiting a familiar place, no matter how special, could never live up to that first experience. However, over time, I have found that I was mistaken. When I returned to my home mountains as a scientist, I was there for a new purpose. It was no longer about perfect camping spots or “bagging” peaks; it was about looking closer for specific clues of ancient mountaineers. With this new task at hand, a new perspective was provided to me, offering the chance to rediscover my home mountains.

Similarly, photography can offer another approach for reimagining a familiar place. When capturing a location, the experience and images created there can change drastically depending upon the interests and focus of the photographer. Bill Bryson taught us years ago that it’s all about the mindset of the journey. Whether it’s between trees in your backyard or between stalls in a foreign market, a camera and an idea can offer the freedom and excitement of seeing a place as if for the very first time once again.

Archaeology, A Vehicle To The World

I use archaeology to travel and to understand, and photography to share what I’ve learned. This is the combination that has worked well for me, but there are plenty of other options out there. If you can find an opportunity that interests you and can carry you around the world, take advantage and go! Combining archaeology and travel photography has allowed me to explore the many facets of a place and to look at its people, architecture, food and setting to paint a complete picture.

People often ask me why I think archaeology is important. How is it relevant in today’s fast-paced and technology-focused world? I typically respond by answering why I travel, believing that the two are interrelated. It is because of context and perspective. It’s the opportunity to embrace diversity and to be able to see people, events and places in both my own life and afar, and to understand where they fit amongst time and place in our fascinating and complicated world. Oh, and because being the first person in hundreds or thousands of years to see something or hold an object or step foot into a place is a pretty cool feeling.

See more of Matt Stirn’s work at mattstirnphoto.com.

The post An Archaeologist’s Perspective appeared first on Outdoor Photographer.

]]>Shooting and editing techniques for more powerful images.

The post Seven Tips For Travel Photography appeared first on Outdoor Photographer.

]]>Here are seven shooting and editing techniques I use for more powerful images.

1. Composition Is Key

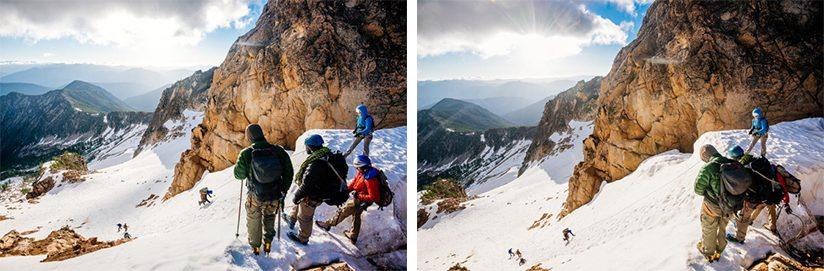

At the end of the day, it’s not the camera with which you shot, the lens or the perfect light, but the image itself that tells the story. Slight changes in angle or timing can mean the difference between the shot you intended and one that falls short. As an artist, it’s your eye that will make the final decision. Which of the two images below holds you the most interested?

2. Nail The Exposure

A slightly darker initial exposure may allow for better detail and color recovery in the brighter parts of your images when developing in post production. Your camera’s light meter electronically assesses a scene and determines what it believes to be the average brightness. Depending on the scene, this can lead to blown out (pure white) areas of your image. By darkening your initial exposure, you can retain image detail and color quality. I’ve found in both SLR and phone camera images that much more detail is retained in the shadows than in the highlights. Below you can see how much we were able to recover in the slightly underexposed foreground, bringing the color and detail back in the field of flowers.

3. White Balance

Similar to exposure, your camera will apply an initial white balance to a scene. Often times, such as at sunset and sunrise or in shaded areas, this measurement can be very off. Using the Temperature and Tint adjustments in Lightroom for mobile we are able to more accurately represent the colors of a scene. I test the Temperature (yellow versus blue) and Tint (magenta versus green) of nearly every image by dragging the sliders both directions to get a quick glance at how the scene’s feeling changes.

4. The Basic Adjustments

Entire articles are dedicated to the “Basic” adjustments (as they are referred to in Lightroom CC and Lightroom for mobile), as they will likely be your most-used editing tools. After adjusting Temperature and Tint, the following adjustments relate to the tonal quality of light and the intensity and quality of color. Note: (+) values equal “brighter” or increased amounts of each setting, and (-) values equal “darker” or decreased amounts.

- Exposure. Acts to lighten or darken the entire image equally.

- Contrast. The difference between the darkest and lightest parts of the image.

- Highlights. The highlights slider recovers detail in the brightest parts of an image.

- Shadows. The shadows slider recovers detail in the darkest parts of an image.

- Whites. This slider allows you to set your white point, which is the brightness value at which the brightest part of the image becomes pure white.

- Blacks. This slider allows you to set your black point, which is the brightness value at which the darkest part of the image becomes pure black.

- Clarity. This slider increases or decreases the mid tone contrast. It is similar to the contrast slider above, but does not affect the brightest or darkest parts of the image.

- Vibrance. The vibrance slider allows you to recover some of the subtle color in your image, bringing back some of the ‘pop’ of color.

Below you’ll see the adjustments I used to edit this image. Generally, the order in which I adjust the sliders is Exposure, Whites, Blacks, Shadows, Highlights, Clarity, Vibrance. The best thing about all these settings being grouped together is that it is quick and simple to jump between settings and see in real time how they are affecting the entire image. When adjusting your Blacks slider further left, you may need to move your Exposure slider further right.

5. Understanding Luminance

Luminance is defined as “the intensity of light emitted from a surface.” We can use Luminance to create more intensity in our skies. By entering the “Color / B&W” tab, you can adjust each color’s Luminance values. By decreasing (sliding to the left) the Blue Luminance slider, you are decreasing the light intensity of the blues of an image, which often lead to more natural and vibrant skies. Below you can see the effects of sliding the Blue Luminance slider to the left and right.

6. You Can Copy And Paste Adjustments

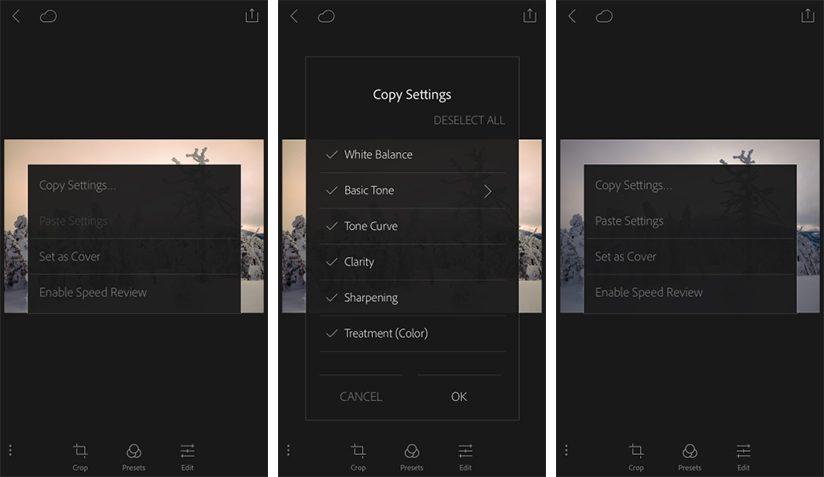

Often you will end up trying several angles and compositions of a very similar scene. On these occasions it can be helpful to apply a basic set of edits to several images. Instead of manually applying the same edits to each image, the Copy and Paste Settings tool in Lightroom for mobile is very helpful. After editing the first image, tap and hold your screen to bring up the menu shown in the screen shots below. Click “Copy Settings” and a menu will prompt which settings to copy. In this case, we want to copy all settings, so we click “OK”. Tap and hold the screen on the photo to which you want to paste the settings, and the pop-up window will now display “Paste Settings” optioin. All the settings from your first image edit will be applied. Repeat as necessary.

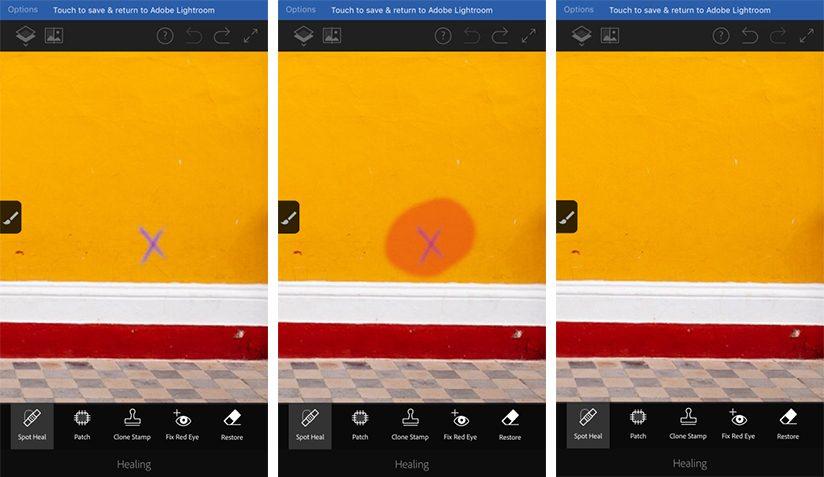

7. Clean Your Image

Inevitably you will come across a scenario where there is something that sneaks into your image that you either missed or cannot control. It could be a tree branch, a dust spot on your lens, or in this case, a distracting marking on the wall of a building. With Photoshop Fix we can quickly and easily remove the distracting element from our scene.

- In Lightroom for mobile, select the “Open In” command (in the upper right corner of the screen). Tap “Edit In” then “Healing in Photoshop Fix”.

- Select “Spot Heal”.

- With your finger, paint over the area you wish to clean up.

- Viola!

- Touch the blue banner at the top of the screen to save and return to Lightroom for mobile.

William Woodward is a lifestyle, travel and adventure photographer currently living on the road full time in his VW Vanagon named “Ruby”. A conscious effort to downsize and simplify has allowed him to focus on art and experiences in the outdoors. For the past year he has been exploring the American West as well as the Canadian Rockies, with side projects in Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Dubai and Mexico. See more of his work at wheretowillie.com

The post Seven Tips For Travel Photography appeared first on Outdoor Photographer.

]]>The post Working With Mixed Light appeared first on Outdoor Photographer.

]]>

| Broad images taken in open shade at midday will have a slightly cool look because the illumination is coming from the blue sky. |

I started my professional photography career back in 1979. That year I sold my first image for publication. In the ensuing 35 years I have been continually selling images as an editorial photographer and a stock photographer, portraying the world as I find it rather than working in the controlled environment of a studio. Along the way I have continually evolved. I embraced digital imaging in 2003 and started to work with video four years ago.

Over those three and a half decades, the definition of what makes one a professional publication photographer similarly has been changing. I say this because, with the democratization of photography through digital imaging and smartphone cameras, it's more important than ever to clarify the definition of just what a pro is.

It used to be a pro was simply someone who was paid for their photographs. Then it became someone who could get the best shot. More recently it was the person who could get the highest quality image in changing situations. In my own experience there is one other under-appreciated definition of what makes a professional publication photographer. In the world of publication photography done outside of a controlled environment, a pro has all the skills noted above. They also must know how to use time of day, and the light that comes with different times of day, to their advantage.

When the midday conditions become too harsh, go into open shade to get richly saturated colors and detailed shots. When the midday conditions become too harsh, go into open shade to get richly saturated colors and detailed shots. |

Yes, every photographer, pro or otherwise, dreams about getting assigned to spend months photographing a given location for an international magazine. The cold reality of the world that I work in is that being given a week to cover a region in India is more typical. In this article, I will be talking about a November 2012 assignment I did for Saudi Aramco World magazine to make still images and video of the Kutch region of Western India.

My assignment was to traverse as much of that area as possible, giving a sample of each place in the form of still images and video clips. My wife, who is from India and has some language facility, was my assistant, guide and occasional translator. We also hired a driver with knowledge of the roads and who had better local language skills, which was all but a requirement to pull off this project in one short week. Due to the many challenges of moving around this part of India at night, we settled on a plan of shooting sunrise through late morning, followed by mid-day drives to the next location, followed by afternoon/sunset/evening shoots.

With the sun just over the horizon, you can create dramatic backlit images with a dark foreground. With the sun just over the horizon, you can create dramatic backlit images with a dark foreground. |

If you look at the map at http://www.saudiaramcoworld.com/issue/201305/ between.salt.and.sea.htm, you'll see the 27 different venues we photographed and recorded on video during the week's shoot. At least half a dozen more were covered, but they did not make it into the final piece, which is typical with any editorial assignment.

Unlike sunrise shots, as the sun gets a little higher in the sky, you will get more light on the ground and longer shadows. Unlike sunrise shots, as the sun gets a little higher in the sky, you will get more light on the ground and longer shadows. |

If you look at the images accompanying this article you will see a small sample of the images I made. Most importantly you will see the images tagged according to the time-of-day categories that I use when blocking out and executing projects like this. I have six categories that I use when thinking of when an image will be made or how I will use a given block of time while on assignment. Those are sunrise, morning, midday reserved for detail shots, which can be the same time as the midday reserved for indoor shots of people, followed by afternoon and sunset/night.

Midday is a GREAT time to shoot portraits of people near windows. When making posed portraits, I use the same type of windows to create dramatic portraits. The directional light that comes in from one side creates evocative portraits. The way I control the impact of that is mostly in how I position my subject in relation to the light source and the background. The final variable is controlling how much or how little of their face do I ask them to turn towards that light source. The degree of this varies based on how I pose them and on how I position myself in relation to them and the light source.

Getting close to sunset, make use of the long shadows and make them part of the composition. Here the shadows create a leading-line effect drawing the eye to the tourist couple being photographed. Getting close to sunset, make use of the long shadows and make them part of the composition. Here the shadows create a leading-line effect drawing the eye to the tourist couple being photographed. |

The Wells Point

While many photographers hew to the idea of only photographing during the so-called Golden Hour, I have always found that time to be too limiting. Yes, the light is warm and beautiful, but it is too short a time for me to work efficiently and there are many other colors I want in my images besides the yellow/orange/red that often dominates that time of day. I work during the golden hour, but I continue working right up to the point where the sun reaches 45 degrees above the horizon. Then I stop working outside until the sun arcs through the sky and reaches that same 45 degree point in the afternoon.

I use something that I call The Wells Point to tell me just when that is, to know how late in the morning I can shoot before the light goes bad, and at what point in the afternoon the light turns good. The Wells Points, as I tell my students, are when the shadow is the same length as the object that casts that shadow. I am 5' 7" so when my shadow is 5' 7" in the morning I stop, and in the afternoon I will start again when the shadow gets to that length or longer.

Following The Wells Point and shooting further into the late morning light and using the early afternoon light after The Wells Point expands my shooting time, which is something critical on shoots like the Kutch project. That same light also has more contrast and yields images that are nicely saturated in terms of their colors. The nice thing about using The Wells Points is the idea works around the world, regardless of season. In the dead of winter in the Northeastern U.S., for example, the sun never gets above The Wells Points, so winter light in places like Boston, New York and Philadelphia is always great in the winter.

As you approach a Wells Point in the afternoon, the light is warmer and much softer than at midday. As you approach a Wells Point in the afternoon, the light is warmer and much softer than at midday. |

With my expansion into video, I've become a bit more disciplined about white balance. I spent years shooting color slides and I once even owned a color meter for fine-tuning my color filtration. So I know about color temperature and white balance. On the other hand, shooting RAW files with the myriad options for correction in post-production had made me a bit loose when it came to color temperature and white balance. While it's technically possible to color correct video, why would I want to spend the time doing that when an extra 30 seconds spent during capture will give me video with the white balance I want.

In some cases changing my position will change the white balance. For example, a mud wall with sunlight bouncing off of it can make or break a video clip depending on how close the subject is standing to that "warm light reflector," so I have to control that variable myself. Similarly, open shade under most awnings tends to be pretty blue during hard midday light. But, controlling where I put myself or my subject can reduce, eliminate or even make that blue color cast a useful part of the narrative I'm creating.

|

Shooting The Video

|

| You can see finished video from the Kutch project at www.aramcoworld.com/issue/201305/kutch-video.htm. The full video includes stills, time-lapse animation and pieces from the 27 shorter videos that are thirty to ninety seconds each. The short vignettes populate the map at: www.saudiaramcoworld.com/issue/201305/ between.salt.and.sea.htm The approach that I took while working on assignment in Kutch, especially in terms of how I allotted my shoots based on time of day and thus the resulting light, should inform the thinking of any established or aspiring publication photographer. The difference between working like a pro and an amateur is as much about managing time (and thus, light) as it is about any other skill. As someone increasingly working in video as a one-man-band, those same skills of time and light management are more important than ever. |

So, when shooting video I follow two rules that organically spill over to make my still photos better. First, I'm constantly checking the white balance of my video clips to make sure my whites are fairly neutral and that I do not have any wild fluctuations in white balance between video clips—if, for example, the inside of a workshop for handmade embroidery is slightly warmer in one corner and a bit more neutral in another corner, I don't care. In fact, that variance, as long as it's not too extreme, gives the final video a more organic feeling. Those lighting situations, where there are extreme changes in white balance, require a custom white balance, which is so easy to do with today's camera, so why not do that?

To me, the big issue is how to accurately judge the white balance and my potential corrections for the videos in question. This is especially challenging when working in bright sun where the back of the camera monitors are hard to read at best. Having a bright electronic viewfinder on my cameras allows me to see the imagery that I've been making through a darkened viewfinder so I can judge the white balance, exposure, etc. Some photographers use magnifiers or external monitors with sun hoods to make this easier.

Two other tools are keys to my success in a project like this—having a camera with an articulating LCD screen and a tabletop tripod. When photographing from high or low, I use the folding screens to compose so as not to contort my body to see through the viewfinder. Once I settle on a composition, I often set up my shot with the camera on my Really Right Stuff Pocket Pod tabletop tripod. It allows me to shoot still images, video and the occasional time-lapse animation and have them all flow together seamlessly.

You can see more of David Wells' photography and video assignments at davidhwells.com. Check out his blog at thewellspoint.com.

The post Working With Mixed Light appeared first on Outdoor Photographer.

]]>The post Traveling The World In B&W appeared first on Outdoor Photographer.

]]>

| Though it was overcast with cloudy skies, the rich diversity of tones provided an ideal backdrop for a black-and-white image of these young lovers on a bridge in the middle of Paris. The light was fairly flat, but the couple and the surrounding scenes were rich with a range of light and dark tones, which I accentuated once I brought the image into Adobe Lightroom. I didn't concern myself that the resulting original file likely would look a little flat. Instead, I focused on carefully composing my shot to capture the momentary gesture of the young girl touching her companion's cheek. |

When we think of travel photography, the first images that flash in our minds are likely in color. Whether the destination is Paris, Morocco, Honolulu or Rio de Janeiro, the images we imagine are undoubtedly influenced by the photographs we've seen in magazines, not least of which is National Geographic, whose photographers have made the use of light and color an art form. As evocative as those color photos are, there are times when a scene is even stronger if it's rendered in black-and-white. The natural world is rich with saturated greens, reds and blues, but sometimes the monochromatic image more adeptly expresses our personal experience of a scene and a moment. It's no less so when we're traveling, even in largely urban environments.

Use Your Nature Skills

The great thing about producing black-and-white travel photography is that you're utilizing the very same experience and skills you practice when you're photographing nature. Your ability to see light and shadow and to build strong, effective photographs of nature are the same skills you need to produce great black-and-white travel images.

I realized the truth of this when I began to photograph nature. I thought I was at a severe disadvantage because I rarely photographed natural landscapes, macro subjects or wildlife. I was nervous that anything I produced would be a bust, but I quickly discovered that everything I had learned about light, contrast, color, composition and foreground and background relationships from travel photography was still at play even though I was photographing in Death Valley or Yosemite. Yes, the subjects were different, but the concepts that make a good photograph were still the same.

It's Still About Light

A great way to begin seeing and photographing in black-and-white is to simply pay attention to the light. Just as with color photography, the early morning and late afternoon deliver strong directional light, which produces strong points of contrast between light and dark. The resulting contrast can help reveal shapes and textures that otherwise would be lost under flatter, even light.

Though it's easy to want to sleep in, especially during our vacations, the choice to rise early and stay up later has its advantages. The magic light during those times is just as magical when color is no longer a factor. Though you may not use it to take advantage of the vibrancy of reds and blues, you're still using that same light to create a different relationship of tones, shapes and patterns.

Whether the shadows are stark or hard as a result of strong directional light or flatter because of a rainy overcast day, the photographs become as much about the range of tones than just the subject or elements within the frame. In fact, the tones themselves become the critical concern as you explore the world in black-and-white.

| This Article Features Photo Zoom |

Use Your Camera To See In B&W

Though an understanding of color theory is always an advantage, it's not a requirement. This is because we can easily set the camera's Picture Style mode to monochrome or black-and-white. This results in the image being played back on the LCD or the electronic viewfinder as a black-and-white. You immediately have a sense of how greens, reds, yellows and other colors will appear in your photograph.

If you're shooting and saving your images as RAW files, you maintain your color originals. The image played back on your screen refers only to the JPEG, which, if you want to retain, means setting your camera to the RAW+JPEG setting. This is a viable choice if you're starting to learn to see in black-and-white. Additionally, you may be quite happy with the black-and-white version created by the camera.

Your camera may provide filter options for its black-and-white setting, including a yellow, green or red filter. I suggest using only the yellow filter if your images include people. Otherwise, the green or red filter can make the resulting skin tones look rather unnatural. Of course, you can use a traditional glass filter, if you prefer.

Pay Attention To The Shadows

One of the best ways to evaluate the quality and the direction of the light is simply to pay attention to what's happening with the shadows. The shadows reveal whether the light is hard or soft and from what direction the light is coming. That information alone can easily determine things as simple as on what side of the street to walk or even in what direction to go exploring.

Shape And Form

The presence of strong shadows can help to accentuate shape and line, but it's not absolutely necessary. Such was the case during several days of my recent trip to Paris, when rain and cloudy skies were the norm. Rather than allow such weather to dissuade me from making good photographs, I chose to emphasize shapes, lines and patterns and micro-contrasts to produce good images of architecture.

Foreground/Background Relationships

When the photograph is stripped of color, the things we choose to include or exclude from the frame become all the more critical. Saturated colors such as reds and yellows can be big visual draws and we can build a composition on that fact. But when color is lacking, it's things like brightness, contrast, pattern and sharpness that instruct the viewer where to look first and how to explore the rest of the frame. In fact, it's the practice of shooting black-and-white that can truly challenge your skills to produce strong and effective compositions.

| This Article Features Photo Zoom |

Postprocessing

The image produced by the camera should be considered a starting point for a final black-and-white photograph. Regardless of how good the image may look on the camera's LCD screen, these images often will require a bit of refining in Lightroom or Photoshop. You want to avoid simply taking your color image and desaturating it to remove all the color. That just makes it a shot without any color. It doesn't really make it a black-and-white image, which requires a more thoughtful conversion.

In Lightroom's RAW converter, I'll make my global adjustments with respect to levels, curves, contrast and sharpness. Then I'll move over to the Black & White Mix module, which allows me to make selective changes based on the original colors within the file. It's a powerful tool, and it allows me to isolate adjustments of contrast in a fast and convenient way. I then can follow up with the Adjustment brush to selectively dodge and burn the image to emphasize and de-emphasize certain elements in the frame.

I'm also a fan of Nik Silver Efex Pro 2, which is one of my favorite plug-ins for converting color images to black-and-white. With its diverse range of presets and customizable adjustment tools, you easily can create unique looks. Both methods can be as easy or as complex as you want to make them.

Dodging And Burning

Remember that the human eye is drawn to the brightest element within the frame and you can use the art of dodging and burning to control the viewer's experience of the photograph. Don't be satisfied with hitting a preset to convert your image from color to black-and-white. The full expression of that moment, that shot, lies in your careful enhancements of the image.

There's an air of the classic, even romanticism, to black-and-white photographs, especially when making images abroad. The choice to document the places we've seen and the people we've encountered in black-and-white provides us with the opportunity to do more than make the typical snapshot. It's a wonderful chance to hone our skills as photographers by making images that leave as much of an impression as the moments that help us to remember.

Ibarionex Perello is a photographer, writer and host/producer of "The Candid Frame" photography podcast (thecandidframe.com). He's also the author of five books, including Chasing the Light: Improving Your Photography with Available Light and his latest, Portraits of Strangers.

The post Traveling The World In B&W appeared first on Outdoor Photographer.

]]>The post Invisible Light appeared first on Outdoor Photographer.

]]>

| Known for her work in remote and exotic parts of the world, Nevada Wier has been experimenting with and refining her infrared work for several years. The photos have a surreal look and a glow that make them positively mesmerizing. Above: Young monk, Thingyan Monastery, Salay, Myanmar, 2009. |

Six years ago, I began exploring the challenge of making the invisible visible—photographing unusual places using a digital camera and the unusual, haunting light of infrared. I'm now a devotee of invisible light!

Oxcart in Ngonegyi Village, Chindwin River, Myanmar, 2013. |

Our visual world is limited to the colors of visible light. Beyond what our eyes can see is the iridescent world of the infrared (IR) spectrum. Infrared light has a longer wavelength than visible light, and is just beyond the range that we humans can detect with our eyesight. IR rests just to the right of visible light on the electromagnetic spectrum chart. For infrared photography, the camera, whether film or digital, needs to be made sensitive to near-infrared wavelengths (700 to 1200 nanometers); far-infrared is the province of thermal imaging, with wavelengths closer to microwave.

Robert W. Wood published the first infrared photographs in 1910, but IR photography was a cumbersome process. In the 1930s, Kodak developed emulsions that were sensitive to infrared light and introduced them to the commercial market. Kodak's black-and-white infrared film was the popular choice, although a number of manufacturers developed different kinds of infrared film.

Great one-horned rhinoceroses, Kaziranga National Park, Assam, India, 2010. |

In 1974, I began my photographic adventures working in the wet darkroom with black-and-white film. I loved the alchemy of the darkroom, watching images miraculously emerge from the stop bath. I spent every spare moment developing film and printing images. By the late 1980s, however, I had abandoned black-and-white film and the darkroom for Kodachrome, a color transparency film. My printing days were over. Travel and color photography were my new passions.

A number of photographers I admired were working with black-and-white infrared film, and I was entranced by their images. However, I wasn't willing to return to the wet darkroom. From 1998 to 2003, I experimented with Kodak Ektachrome Professional Infrared/EIR transparency film, which could be developed in standard E-6 chemistry. The images didn't have an ethereal feeling, but they did have vivid, kooky, mostly unpredictable colors—greens became reds, brown water became blue, etc. While I loved it, I couldn't find a commercial use for it.

Camel trader at Pushkar Fair, Rajasthan, India, 2010. |

I switched 100% to digital cameras in 2004. Not only did I prefer the expanded dynamic range of digital images and exposure flexibility, I also knew I was finally going to be able to print my own color images. I had rarely made a print from a color transparency, and after using such beautiful black-and-white papers as Ilford Portriga Rapid and Agfa Brovira, I couldn't bear to print my color images on the generic "matte or glossy." But now, with digital, the world of color printing was in a renaissance, with new, stunning archival papers and inks, as well as portable color printers. I was out of the darkroom and into The Grayroom (yes, my walls are 18% gray). I was coming full circle back to my love of printing. I reread Ansel Adams books on printing, studied with some present-day printing masters, experimented with papers and learned enough of Photoshop to craft a print. Crafting a fine-art print is similar to sculpting. The image on a print has to have a soul of its own, and the print of that image needs to stand alone like a sculpture, with presence and depth.

In 2007, about the same time as I had my first show of color images, I discovered that digital cameras were the perfect device for recording the hidden beauty of infrared light, and there were many more creative possibilities than before.

Digital cameras are so sensitive to infrared light that manufacturers place a filter in front of the sensor to block the infrared light from spoiling regular photographs. By removing this filter and replacing it with one that blocks most of the visible light, the photographer is able to record near-infrared light with a bit of visible, deep red light. The result is a surreal image with a bit of color, usually shades of blues and amber with occasional magenta. (There are a number of places where you can convert a digital camera to infrared red; I use a company called LifePixel, www.lifepixel.com.)